Abstract

Modern Education system is based on scientific

principles which most business schools accept for academic credibility.

However, Leadership Education is more of an art than a science and needs to be

taught like an art.

Next we discuss the reasons modern business schools

fail to produce leaders whose careers, in general are successful as compared to

their counterparts without business school education. We study the causes of

decline of business school education and discuss some remedial measures.

Assumptions

While references and explanations are given to most

statements in this paper, there are 3 fundamental assumptions I make without

any explanation.

- Human behavior is unpredictable in nature

- "Leadership” and “Leadership Education” are not entirely the same thing and may have differences

- Leadership Education is primarily delivered by Business Schools

Leadership

Education as an Art

The current Education system is predicated on the

idea of academic ability. Reason being that the whole system was invented round

the world in the 19th century prior to which there were no uniformly

structured public systems of education. They all came into being to meet the

needs of industrialism.

The hierarchy came to be rooted in two ideas. One,

the most useful subjects were science, technology and math, which came to

define academic institutions and academic credibility. Two, the idea of

academic ability came to be as a measure of intelligence, because the

universities designed the system in their image. The whole system of public

education around the world was a protracted process of university entrance (Sir

Ken Robinson 2006).

In 1959, the Gordon and Howell report described

American business education as “a collection of trade schools lacking a strong

scientific foundation” (Zimmerman, 2001). The Gordon and Howell Report and

funding from the Ford Foundation and the Carnegie Council (Pierson, 1959)

started business schools on their continuing trajectory to achieve academic

respectability and legitimacy on their campuses by becoming applied social science

departments. In the process of achieving academic legitimacy, business schools

took “on the traditions and ways of mainstream academia” (Crainer &

Dearlove, 1999). Quantitative, statistical analyses gained prominence, as did

the study of the science of decision making. In both their teaching and

research activities, business schools “enthusiastically seized on and applied a

scientific paradigm that applies criteria of precision, control, and testable

models” (Bailey & Ford, 1996).

However, unlike scientific research, research at a

b-school need not necessarily be implementable or even reproducible elsewhere.

Infact, results observed by a company might not necessarily be implementable in

another. This is because traditionally, science

is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of

testable explanations and predictions (Wilson, 1998); while leadership deals

with humans behavior which denies predictability.

Moreover, scientific method works on the principle

of reproducibility, which govern that

any experiment has the ability to be entirely reproduced, in similar

environments, at any point in space and time, either by the researcher or

someone working independently. The unpredictability of human emotions and

mindsets do not grant this right to leadership theories based on scientific

principles.

If Leadership Education were to be visited by an

alien who asked what is it for, looking at the output, who does everything they

should, who are the winners, one would conclude that the whole purpose of

Leadership Education throughout the world is to produce university professors

who teach and research on Leadership Education.

Leadership Education is more of an art or craft than

a scientific study. When an artist breaking the traditional rules of her/his

craft does not make a bad art, but rather a new art which may or may not be

appreciated. However, scientific theory is either right or wrong, and remains

so at any point of time anywhere in the universe. Leadership decisions, like

art, change credibility with context, audience, and time. Hence, it is safe to

say that concrete theories are not the path to follow for Leadership Education,

but rather contextual stories help develop leadership. One may read all

literature available on Leadership and still, going against the theorized

principles might make good decisions.

Leadership, like any art, is better learnt with

practice than simply studying the available models. Leadership problems demand

imagination, creativity and out-of-the-box thinking for their solutions.

Teaching Leadership as a science with theories and numbers sounds good for

academic credibility, but not for real world applications. That is similar to

teaching dance via lectures in the field of human anatomy; or teaching cycling

with an expectation that once one has learnt all the principles of physics and

balance, one can learn to ride a bicycle without falling.

Why Business

Schools fail to produce good Leaders

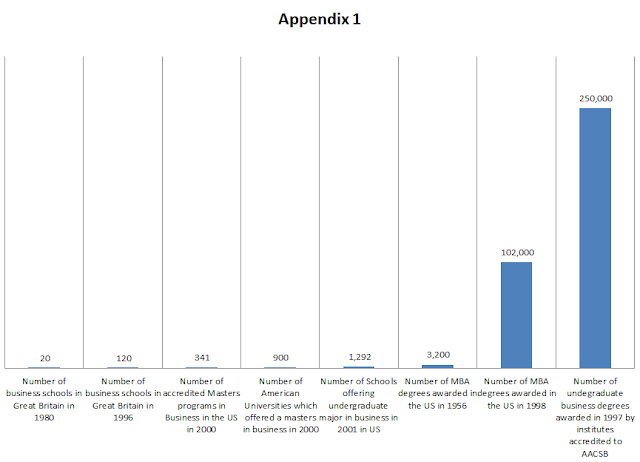

In the last half-century, the business of business

schools has grown exponentially. Between 1956 to 1998, the number of MBA

degrees awarded in the US grew from 3200 to 102000, i.e. by almost 32 times

(Zimmerman, 2001). By 2001, 92% of all accredited colleges and universities in

the US offered an undergraduate major in business (US News and World Report.

2002). In Britain, the number of business schools rose by 6 times from 20 to

120 between 1980 and 1996 (The Economist, 1996).

Since the mid-1980s, 36 Americans have each given

more than $10M to business schools (The Economist, 1996). In the United

Kingdom, business schools “are among the top 50 exporters, attracting over

$640M a year from other countries” (Crainer & Dearlove, 1999). A

McKinsey-Harvard report from 1995 estimated that non-degree executive education

“generated around $3.3 billion and was growing at a rate of 10% to 12%

annually” (Crainer and Dearlove, 1999).

The business and growth of business schools is

depicted in Appendix 1.

Given the overbuilt setup of the MBA industry

(Gaddis, 2000), and the huge profit-making sector it has turned out to be, it

is not surprising that so many MBA schools have come up in such a short span of

human existence. Usually, business schools charge between $7k to $110k for an

MBA degree. This is much more than a regular engineering degree and lacks

infrastructure such as laboratories and high-costing experimental equipment.

The rationale behind this is that business schools offer faculty who are

capable to earn more than engineering faculty in their respective areas. Also,

a business school graduate, in general, tends to earn more than an engineering

graduate. While this is true in most cases, this has led to business schools as

a fast-profit generating enterprise where sometimes small incapable players

jump in to have a slice of the pie.

From data gathered from Business Insider,

Businessweek, The Economist, US News, Forbes and Financial Times (2011) on 341

US business schools, a study conducted shows that judging on the basis of

starting salaries as a measure of Education competency, most business schools

fail as compared to the premier ones.

As with any status based system, status is achieved

partly through the status of the organizations with which one associates

(Podolny 1994). However, most business schools fail to even come close to the

standards set by the premier business schools.

Given the vast supply of an MBA degrees and everyone

wanting one, the degree is being sold

easily, however, each MBA degree does not have the same value as conferred in

the above study. Low cost price and high selling price of business education

makes it a “cash cow” at many universities. This is also proved by the numbers

of programs which have proliferated including, more recently, part-time,

evening, and weekend programs; executive MBAs; and expansion of existing

programs. This huge supply of MBAs automatically translates into less advantage

in terms of salary or other career outcomes for MBA graduates.

The current system of Management Education has

created a bottleneck for competition even in good accredited universities where

it’s difficult to get in but getting insanely easy, making grades or completion

useless measures of learning. Grade inflation is pervasive in American higher

education (Kuh & Shouping, 1999; Muuka, 1998; Redding, 1998). As a consequence, almost no one fails out of

MBA programs, which means the credential does not serve as a screen or an

enforcement of minimum competency standards. If the MBA degree doesn’t really

distinguish among people then it is no surprise that it doesn’t have much

affect on career outcomes.

Armstrong, a professor who has taught MBAs for more

than 30 years observed, ‘In today’s prestigious business schools, students have

to demonstrate competence to get in, but not to get out. Every student who

wants to (and who avoids financial and emotional distress) will graduate. At

Wharton, for example, less than 1% of the students fail in any given course, on

average… the probability of failing more than one course is almost zero. In

affect, business schools have developed elaborate and expensive grading systems

to ensure that even the least competent and least interested get credit

(1995).’

In India, a city named Kota has come up with a

network of non-accredited educational institutes which coach candidates for India’s most competitive university entrance

examination, IIT-JEE where the intake is almost 1% of the appearing candidates

and is decreasing annually by about 0.05% due to increasing number of

candidates.

Kota specializes in coaching institutes which train students for IIT-JEE. In every

institute, there are batches of

students. Monthly tests determine the batches of each student. For example, the

top 100 scorers will be put in one batch, the next hundred in another batch and

so on up to the last hundred. This creates a discriminatory class division of

which every one of the 80,000 students of Kota are a part. While it becomes

highly depressing for students in the bottom-most batches, it tells the

students where they presently stand by the IIT-JEE standards and which of them

need to work the hardest.

Often, this discrimination on the basis of knowledge

results in severe anxiety, depression and even suicides. While this is too

extreme a measure to be taken at university level, it clearly shows that there

needs to be a regular check on students academically to keep them in check and

to let them know where they currently stand, so as to let them know what the

prospects of their current position are. In business schools, this

characteristic of education seems to be lost and is resulting in a pool of MBAs

who do not know where they stand when it comes to looking for career

opportunities.

References

- AACSB Newsline. 1999. Number of undergraduate business degrees continue downward plunge, while MBA degrees awarded skyrocket. Doctoral degrees on the decline.

- Armstrong J S. 1995. The devil's advocate responds to an MBA student's claim that research harms learning. Journal of Marketing. 59: 101-106

- Bailey J & Ford C. 1996. Management on science versus management as practice in postgraduate business education. Business Strategy Review. 7(4); 7-12

- Crainer S & Dearlove D. 1999. Gravy trainings: Inside the business of business schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Boss

- Gaddis P O. 2000. Business schools. Fighting the enemy within. Strategy and Business. 21(4): 51-57

- Gordon R & Howell J. 1959. Higher Education for business, New York Columbia University Press.

- Kuh G D & Shouping S 1999. Unravelling the complexity of the increase in college grades from the mid-1980s to the mid 1990s. Educational Evaluation & Policy Analysis. 21: 297-300.

- Pfeffer J & Fong C T. 2002. The End of Business Schools? Stanford University.

- Pierson R C. 1959. The education of American businessmen. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Podolny J M. 1994. Market uncertainty and the social character of economic exchange. Administrative Science Quarterly. 39; 458-483.

- Sir Robinson K. 2006. Do Schools Kill Creativity? TED.

- The Economist. July 20, 1996. Dans and Dollars.

- US News and World Report. 2002. Top Business Schools: 2002.

- Wilson E O. 1998. Consilience: The Utility of Knowledge. New York, NY: Vintage Books. 49-71.

- Zimmerman J L. 2001. Can American business schools survive? Rochester NY: Unpublished manuscript, Simon Graduate School of Business Administration